On the concept of strategic surprise

In international relations research, “strategic surprise” is often understood as an event that is sudden, beyond the ability to predict normally, directly affecting national interests and national security, thereby forcing the country to fundamentally adjust its foreign policy and strategic orientation (1) . Even with full information, policymakers can still fall into a passive state due to cognitive biases and time pressure, leading to the inability to correctly perceive the nature of new threats.

Similarly, in her important study of the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, scholar Roberta Wohlstetter pointed out that having more information does not always help prevent strategic surprises from occurring (2) . In fact, failure to predict and prevent strategic surprises is often not due to a lack of information, but due to the large amount of “noise” that is inevitable when processing a huge amount of information. This challenge is even more acute in the current digital age, when countries are faced with a huge flow of information and data from many different sources, and at the same time, the speed of change in the international situation is also increasing exponentially.

From another perspective, scholar Erik Dahl emphasizes two key factors in preventing strategic surprise: One is accurate information at the tactical level; two is the level of policy makers' receptivity to warnings (4) . By comparing the US participation in the Pearl Harbor attack and the Midway naval battle in the Pacific theater, Erik Dahl points out that success in preventing strategic surprise depends not only on the ability to analyze the overall strategy, but also requires specific, actionable information and the readiness of leaders to receive and process information. This theory is especially valuable in the current context, when countries are facing many new types of security challenges, from terrorism to cyber attacks, requiring a harmonious combination of information gathering capabilities and timely decision-making capabilities of the policy-making apparatus.

In general, studies show that strategic surprise is multidimensional and complex, and can originate from many different causes. This is a comprehensive challenge that includes cognitive, organizational and systemic factors, requiring countries to build a comprehensive process and system that combines the capacity to collect and process detailed information, the ability to analyze strategy as well as flexibility in the decision-making process. In the increasingly uncertain global geopolitical context, with the emergence of breakthrough innovations such as artificial intelligence (AI), big data and new forms of conflict in cyberspace, the ability to identify and respond to strategic surprise is becoming one of the core competencies to ensure national security.

International experience in responding to strategic surprises

A study of international conflicts has shown that there were up to 68 recorded cases of strategic surprise in the 20th century, often appearing after periods of tension and crisis (4) . This characteristic suggests a fundamental paradox in the study of strategic surprise, which is that even when warning signs appear, states can still fall into a passive situation due to limitations in identifying and reacting to these signs.

Since 1945, the nature of strategic surprise has changed fundamentally. First, the scope of strategic surprise has expanded beyond the traditional military sphere, including terrorist attacks, cyber attacks, and economic and financial crises with geopolitical implications. Second, technology has become an important variable, creating new tools for forecasting and prevention, and opening up new channels of attack and surprise. Third, regional conflicts, although limited in scale, can have global strategic consequences through the chain effect and the increasingly interconnectedness of the international system.

The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 showed that strategic surprise can arise from countries misjudging each other’s risk tolerance. The aftermath of the crisis led to the establishment of a “hotline” between the Soviet Union and the United States and a regular dialogue mechanism between the two superpowers, as well as the birth of many treaties on nuclear arms control in the following decades (5) .

Meanwhile, the 1973 Yom Kippur War between Arab states and Israel is a classic example of how a coalition of states can create strategic surprise by exploiting “blind spots” in the strategic thinking of its adversary. After its overwhelming victory in the 1967 Six-Day War, Israel developed a “defense concept” based on its belief in absolute military superiority and an early warning doctrine (6) . Egypt and Syria successfully exploited this weakness in thinking, conducting a sophisticated months-long diversionary campaign that included more than 40 large-scale exercises along the border, gradually causing Israel to lose its guard against these military activities. At the same time, Egypt and Syria also took advantage of cultural, religious (choosing the Yom Kippur holiday) and geo-strategic (attacking simultaneously on two fronts) factors to maximize the element of surprise.

The experience of this war led to a fundamental change in Israel’s approach to the problem of strategic surprise (7) . First, Israel established a unit dedicated to challenging prevailing strategic assumptions, in order to reduce blind spots in intelligence analysis. Second, it built a multi-layered early warning system, combining both technological and human factors, with a special focus on monitoring small changes in the strategic environment. Third, it developed a “layered defense” doctrine, not relying on a single layer of defense, no matter how sophisticated. This lesson is said to still be valuable for small and medium-sized states in the current context.

Entering the 21st century, the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in the United States (September 11, 2001) posed a new challenge in identifying and responding to strategic surprises. The surprise did not lie in the collection of information because there were many intelligence reports mentioning the terrorist organization Al Qaeda in the period before the attack, but in the inability to connect the fragmented pieces of information into a comprehensive picture (8) . The report of the US National Commission on Terrorist Attacks on the United States (also known as the 9-11 Commission) established by US President George Bush in 2002 also stated that this was the result of a "failure of imagination" and limitations in the organizational structure of the US intelligence agency, hindering the sharing of important information throughout the entire network of security agencies. Soon after, the United States implemented the most sweeping reform in the history of the intelligence industry, including the establishment of a Director of National Intelligence (DNI), restructuring information sharing processes, and building an interagency analysis center.

While the United States focuses on large-scale institutional reform, some small and medium-sized countries have developed different approaches to dealing with strategic surprises. Singapore, with its sensitive and vulnerable geostrategic location, has built a “comprehensive warning” system based on three pillars. First, developing strategic forecasting capabilities through the National Scenario Office and the National Situation Center, focusing on scenario building and regular response exercises. Second, enhancing the self-reliance of the entire society through the “total defense” program, helping to prepare the people’s mentality and response capacity for emergencies (9) . Third, maintaining a diverse network of foreign relations to have multiple sources of information and support when needed. In addition, Singapore has also proactively interwoven its interests deeply and comprehensively with major countries by attracting leading corporations from the US, China, and the European Union (EU) to set up headquarters. The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Forum (APEC), the Pacific Economic Cooperation Council (PECC) and many other international institutions are also headquartered in Singapore.

From international experience, some common features can be drawn in effective approaches to strategic surprise.

First, the importance of building a multi-layered early warning system that relies not only on technology or technical intelligence, but also on a variety of sources of information, from diplomacy to academic analysis. The experiences of Israel and Singapore show that establishing expert groups tasked with challenging widely accepted strategic assumptions is crucial to avoiding “blind spots” in policymaking.

Second, countries that are successful in dealing with strategic surprises often develop a comprehensive approach that goes beyond military and technological solutions alone. While maintaining traditional deterrence and defense capabilities, these countries place special emphasis on enhancing the resilience of the entire society (societal resilience). The “total defense” model of the Nordic countries is considered a typical example. Sweden and Finland have developed systematic programs to enhance the awareness and resilience of their people in crisis situations, from armed conflicts to non-traditional security challenges, such as cyber attacks or information warfare (10) . This approach helps create an important “buffer”, contributing to minimizing the impact of strategic shocks and enhancing the country’s ability to adapt to unexpected situations.

Third, in the context of globalization and increasing interdependence, small and medium-sized states have developed innovative ways to enhance their predictability and response capabilities. For example, they have built a diverse network of partners, actively participated in regional and international cooperation mechanisms, and maintained flexibility in their foreign policies to avoid over-dependence on any one partner.

Fourth, building the capacity to respond to strategic contingencies is a continuous and adaptive process. Threats are increasingly diverse and complex, requiring a comprehensive and flexible approach, capable of integrating new lessons and adapting to changes in the strategic environment. This is valuable experience that small and medium-sized countries can refer to in the process of perfecting the capacity to forecast and respond to strategic contingencies in the new context.

Avoid being passive and surprised in new situations

Vietnam is facing an increasingly complex and unpredictable international environment. First, competition between major powers, especially between the US and China, is creating new pressures and challenges for small and medium-sized countries in the region. This trend is not only manifested in traditional geopolitics, but also clearly demonstrated in the fields of technology, trade and global supply chains. Second, non-traditional security challenges, such as climate change, cyber security, epidemics, etc., are posing new requirements for forecasting and response. Third, the East Sea issue continues to evolve in a complex manner, with intertwined challenges between territorial sovereignty, freedom of navigation and management of marine resources.

In addition, conflicts and “flashpoints,” from Ukraine to the Korean Peninsula, demonstrate that the regional security environment can change rapidly and profoundly. At the same time, the development of new applications, such as AI, hypersonic weapons, and cyber capabilities, is creating new challenges in identifying and responding to strategic surprise. In this context, the ability to maintain strategic initiative and avoid passivity and surprise becomes more important than ever.

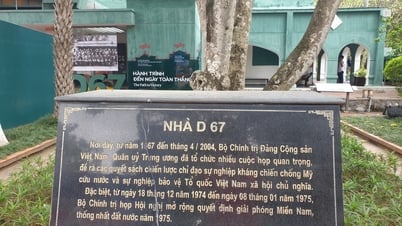

During the revolutionary period, President Ho Chi Minh demonstrated a profound strategic vision and the ability to predict and seize opportunities skillfully, demonstrated through many important historical decisions, such as launching the August General Uprising in 1945 and the National Resistance War in 1946. Inheriting and developing that ideology in new conditions, the concept of "not being passive or surprised" was formalized in Resolution No. 08-NQ/TW, dated July 12, 2003, of the 8th Central Conference of the 9th tenure, on "Strategy for protecting the Fatherland in the new situation" (11) . In the international context at that time, with complicated developments after the event of "September 11, 2001" and the increasing trend of military intervention in the world, the Communist Party of Vietnam emphasized the importance of "timely handling all seeds of insecurity, not being passive or surprised". This is an important development in the strategic thinking of the Communist Party of Vietnam, reflecting an increasingly profound awareness of the complex and unpredictable nature of the international security environment.

Through congresses, from the 10th Congress (2006) to the 13th Congress (2021) of the Party, this viewpoint continues to be consistently mentioned and developed more deeply in the Resolutions of the 8th Central Committee, 11th and 13th tenures on "Strategy for protecting the Fatherland in the new situation", emphasizing the task of preventing and repelling the risk of war and conflict "early and from afar" to proactively prevent, detect and effectively handle strategic surprises and sudden events. Notably, this phrase appears in two main contexts: One is when assessing the world and regional situation with many unpredictable and difficult-to-forecast developments; two is in the guiding principles on national defense and security, especially related to challenges regarding sovereignty over seas and islands and strategic competition between major countries. At the 13th National Congress, our Party added the element of "maintaining strategic initiative" (12) , reflecting the development in awareness from a defensive to a proactive stance in responding to strategic challenges (13) .

In the speeches of the late General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong at the Military-Political Conference of the entire army since 2016, "not being passive or surprised" was emphasized as "a very important and vital strategic task" (14) . In particular, at the 32nd Diplomatic Conference (December 19, 2023), the late General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong emphasized the requirement to "regularly monitor developments and correctly forecast the development direction of the external situation and especially correctly assess the impacts on Vietnam so as not to be passive or surprised and always stay calm and alert to seize opportunities and advantages, overcome difficulties and challenges" (15) . On October 31, 2024, during a thematic discussion with the class of Central Committee members planning for the 14th tenure on "the new era, the era of national rise", General Secretary To Lam commented that in the context of the world undergoing epochal changes, "challenges are more prominent and new opportunities may still appear in the moments between sudden changes" (16) . During a working session with the Central Military Commission Standing Committee (August 2024), General Secretary To Lam emphasized the importance of "Timely identifying, properly handling, harmoniously and flexibly partners and subjects, avoiding passivity and surprise; preventing the risk of conflict and confrontation, avoiding isolation and dependence" (17) .

From the above-mentioned process of developing strategic thinking, together with new challenges in the current situation, it is necessary to affirm that strengthening the capacity to prevent and respond to strategic surprises requires a comprehensive, systematic and flexible approach. This approach needs to harmoniously combine institutional building, resource development and forecasting capacity improvement, while ensuring consistency from thinking to action throughout the entire political system. On that basis, it is possible to propose some implications to strengthen Vietnam's capacity to prevent and respond to strategic surprises in the coming time.

Firstly, continue to promote education and raise awareness of the entire Party, people and army about traditional and non-traditional security challenges and the role of strategic forecasting. This is not only the task of specialized agencies, but also needs to be identified as the responsibility of the entire political system, associated with strengthening the national defense posture and a solid people's security posture. In addition, focus on building a "people's heart posture", promoting the combined strength of the great national unity bloc in detecting, providing information and participating in preventing risks and challenges to national security. Thereby, contributing to building political and spiritual potential and a solid foundation for the cause of protecting the Fatherland "early, from afar" in the new situation.

Second, focus on improving the country's self-reliance in key areas, from economy, technology to defense and security. International experience shows that the ability to respond to strategic surprises depends not only on forecasting capacity, but also requires a solid spiritual, material and technological foundation and the self-reliance capacity of the entire society, to ensure resilience against potential shocks. In particular, developing the defense industry, mastering a number of core technologies and building strategic reserve capacity are of particular importance.

Third, continue to promote the motto of “adapting to all changes with the unchanging” in foreign relations. This requires both upholding the basic principles of an independent, self-reliant, multilateral, and diversified foreign policy and being flexible in responding to complex developments in the situation. In particular, it is necessary to strengthen security cooperation and information sharing with strategic and comprehensive partners, contributing to enhancing the ability to grasp information in a timely manner and expanding the space for handling complex situations. To do this, it is necessary to create an increasingly close interweaving of interests and enhance political trust in sharing strategic information.

Fourth, perfect the mechanism for coordination and inter-sectoral information sharing in strategic forecasting, in the direction of closely combining foreign affairs, defense, security and strategic research agencies. Building a multi-layered early warning system capable of integrating and processing information from many different sources is an urgent requirement in the current context. In addition, improving the capacity to handle crises (including media crises) through scenario-based exercises. In particular, increasing investment in building high-quality strategic research agencies, playing an effective role in connecting academic research and policy making, contributing to improving the country's capacity to forecast and early identify strategic contingencies.

Fifth, promote the modernization of information analysis and processing. In the context of increasingly large amounts of information and rapidly changing situations, the application of advanced achievements such as AI in big data analysis, combined with improving the judgment and forecasting capacity of the team of experts, is an inevitable requirement. This not only helps to improve the speed and accuracy in detecting early warning signs, but also enhances the ability to forecast the development trend of the situation, thereby proposing timely and effective response plans.

In the context of increasingly complex and unpredictable developments in the world and the region, researching and responding to strategic surprises has become an urgent requirement for each country. From the awareness of "not being passive or surprised" to the policy of "maintaining strategic initiative" and the motto "using the unchanging to respond to all changes", our Party has made important developments in strategic thinking. The realization of this guiding viewpoint requires the efforts of the entire political system and close coordination between agencies, departments, ministries and branches in improving the capacity to forecast and handle situations. Thereby, Vietnam will firmly respond to all challenges, effectively take advantage of development opportunities, and successfully carry out the two strategic tasks of building and defending the Socialist Republic of Vietnam./…

-----------------

(1) Michael I. Handel: “Intelligence and the problem of strategic surprise”, The Journal of Strategic Studies 7, No. 3, 1984, pp. 229 - 281

(2) See: Wohlstetter, Roberta: Pearl Harbor: warning and decision, Stanford University Press, 1962

(3) See: Erik J. Dahl: Intelligence and surprise attack: Failure and success from Pearl Harbor to 9/11 and beyond, Georgetown University Press, 2013

(4) See: Stanley L. Mushaw: “Strategic Surprise Attack”, Naval War College Newport Advanced Research Program, 1989

(5) Jonathan Colman: Cuban Missile Crisis : Origins, Course and Aftermath, Edinburgh University Press, 2016

(6) See: Ephraim Kahana: “Early warning versus concept: The case of the Yom Kippur War 1973”, Intelligence and National Security 17, No. 2, 2002, pp. 81 - 104

(7) See: Itai Shapira: “The Yom Kippur intelligence failure after fifty years: what lessons can be learned?”, Intelligence and National Security 38, No. 6, 2023, pp. 978 - 1,002

(8) Thomas H. Kean - Lee Hamilton, The 9/11 commission report: Final report of the national commission on terrorist attacks upon the United States, Vol. 1. Government Printing Office, 2004.

(9) Ron Matthews - Nellie Zhang Yan: “Small country “total defence”: a case study of Singapore”, Defence Studies 7, No. 3, 2007, pp. 376 - 395

(10) Alberto Giacometti - Jukka Teräs: Regional economic and social resilience: An exploratory in- depth study in the Nordic countries, Nordregio, 2019

(11) Dang Dinh Quy: “Approaching the thinking about “partners” and “objects” in the new context”, Electronic Communist Magazine, January 13, 2023, https://www.tapchicongsan.org.vn/media-story/-/asset_publisher/V8hhp4dK31Gf/content/tiep-can-tu-duy-ve-doi-tac-doi-tuong-trong-boi-canh-moi

(12) Documents of the 13th National Congress of Delegates, National Political Publishing House Truth, Hanoi, 2021, vol. I, p. 159

(13) Nguyen Ngoc Hoi: “The viewpoint of “proactively preventing the risks of war and conflict early and from afar” at the 13th National Party Congress”, National Defense Magazine, June 5, 2021, http://m.tapchiqptd.vn/vi/quan-triet-thuc-hien-nghi-quyet/quan-diem-chu-dong-ngan-ngua-cac-nguy-co-chien-tranh-xung-dot-tu-som-tu-xa-tai-dai-hoi-xiii-cua-dang-17139.html

(14) VNA: “Full text of General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong's speech at the 2016 Military-Political Conference of the Whole Army”, People's Army Newspaper, December 13, 2016, https://www.qdnd.vn/quoc-phong-an-ninh/tin-tuc/toan-van-phat-bieu-cua-tong-bi-thu-nguyen-phu-trong-tai-hoi-nghi-quan-chinh-toan-quan-nam-2016-494879

.

(16) GS, TS. Ky-nguyen-moi-ky-nguyen-vuon-minh-tua-dan-toc-ky-nguyen-phat-trien-giau-manh-duoi-su- lanh -dao-cam-quyen-cong-cong-cong-san-xay-dung -thanh-viet-viet-vie

(17) "General Secretary, President To Lam work with the Central Military Commission Standing Committee", Government Electronic Newspaper, dated August 28, 2024, https://baochinhphu.vn/tong-bi-thu-chu-tich-nuoc-to-lam-lam-viec-voi-ban-thuong-vu-uy-uy-trung-102240828091158399.htm.htmm.htmmm

Source: https://tapchicongsan.org.vn/web/guest/the-gioi-van-de-su-kien/-2018/1075702/bat-ngo-chien-luoc-trong-quan-quoc-te-va-mot-so-ham-y-chinh-sach.aspx.aspx.

![[Photo] Chinese, Lao, and Cambodian troops participate in the parade to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Liberation of the South and National Reunification Day](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/30/30d2204b414549cfb5dc784544a72dee)

![[Photo] Cultural, sports and media bloc at the 50th Anniversary of Southern Liberation and National Reunification Day](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/30/8a22f876e8d24890be2ae3d88c9b201c)

![[Photo] The parade took to the streets, walking among the arms of tens of thousands of people.](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/30/180ec64521094c87bdb5a983ff1a30a4)

![[Photo] Performance of the Air Force Squadron at the 50th Anniversary of the Liberation of the South and National Reunification Day](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/30/cb781ed625fc4774bb82982d31bead1e)

Comment (0)