Writer Nguyen Phan Que Mai

There were many times when the mother jumped into a personal shelter carrying her unborn child to avoid bombs.

Mom told me about the times she had to take her students to evacuate high in the mountains, avoiding bombs while teaching.

Mom told about the long years when she waited for her real brother - Uncle Hai - who joined the army in the South to participate in the war.

Mom told about the boundless happiness of April 30, 1975, when she received the news that the war was over.

Bomb craters and the desire for peace

I saw the yearning for eternal peace not only in Vietnam but also on earth through the stories my mother told. That peace would ensure that no mother on earth would lose her child to war.

I also saw the longing for eternal peace in the eyes of grandmothers, mothers, wives, and sisters in my village of Khuong Du.

During my childhood years, I silently watched those women standing in front of the gate every day waiting for the men of their families to return from the war.

They just wait, day after day, month after month, year after year. I see the pain of war in the mourning scarves of families whose loved ones will never return, in the broken bodies of war veterans.

In 1978, a little girl of 6 years old, I boarded a train with my parents from the North to the South, to create a new life in the southernmost region of the Fatherland - Bac Lieu . In my mind, the giant bomb craters still lie there in the middle of the green rice fields.

As I crossed the Hien Luong Bridge, the bridge that divided Vietnam into two halves during the 20 years of war, many adults around me burst into tears. In their tears, I saw the desire for peace, that Vietnam would never again suffer the bloodshed of war.

I longed for peace in my family’s rice field in Bac Lieu. That field was located on a dike that my father, my mother and my brothers had reclaimed. That field used to be a shooting range for the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. When we reclaimed the land to plant rice and beans, we had to dig up thousands of shell casings.

Touching the shells and unexploded bullets, I shuddered as if touching death. And I secretly wished that one day on this earth, everyone would put down their guns and talk to each other. And love and understanding would dissolve violence.

Journey to tell stories of peace

In my memory of the first days in Bac Lieu, there was the image of a woman selling sweet potatoes, alone with a heavy shoulder pole, walking alone. It seemed that she had come from a very far place to be able to reach the road running in front of my house.

Her feet were worn out, dry and dusty, in a pair of worn-out slippers. My mother always bought them from her, because she knew that her two sons had gone to war and had not returned. She had not received a death notice and was still waiting. As the years passed, when her waiting was exhausted, she chose to end things for herself. One day, on my way to school, I saw her body hanging from a tree.

She took her waiting with her to the other world . I stood there, silently looking at her dry feet. And I imagined her walking her whole life in search of peace. I carried her pain into my writings.

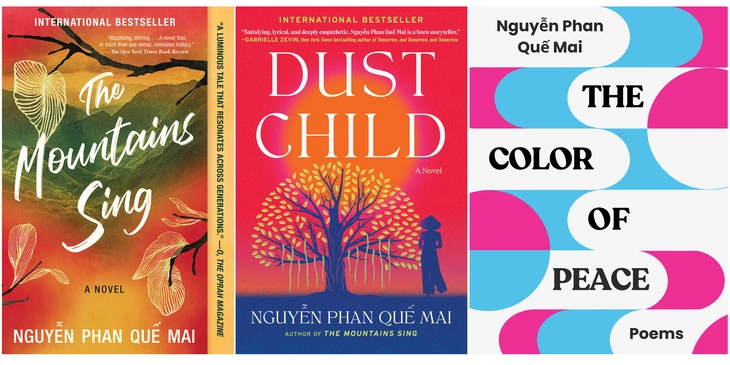

My first two novels, The Mountains Sing and Dust Child (tentative Vietnamese title: Bí mật đầu đầu đầu), are about the losses of women who have to go through war, regardless of which side their loved ones have to fight for.

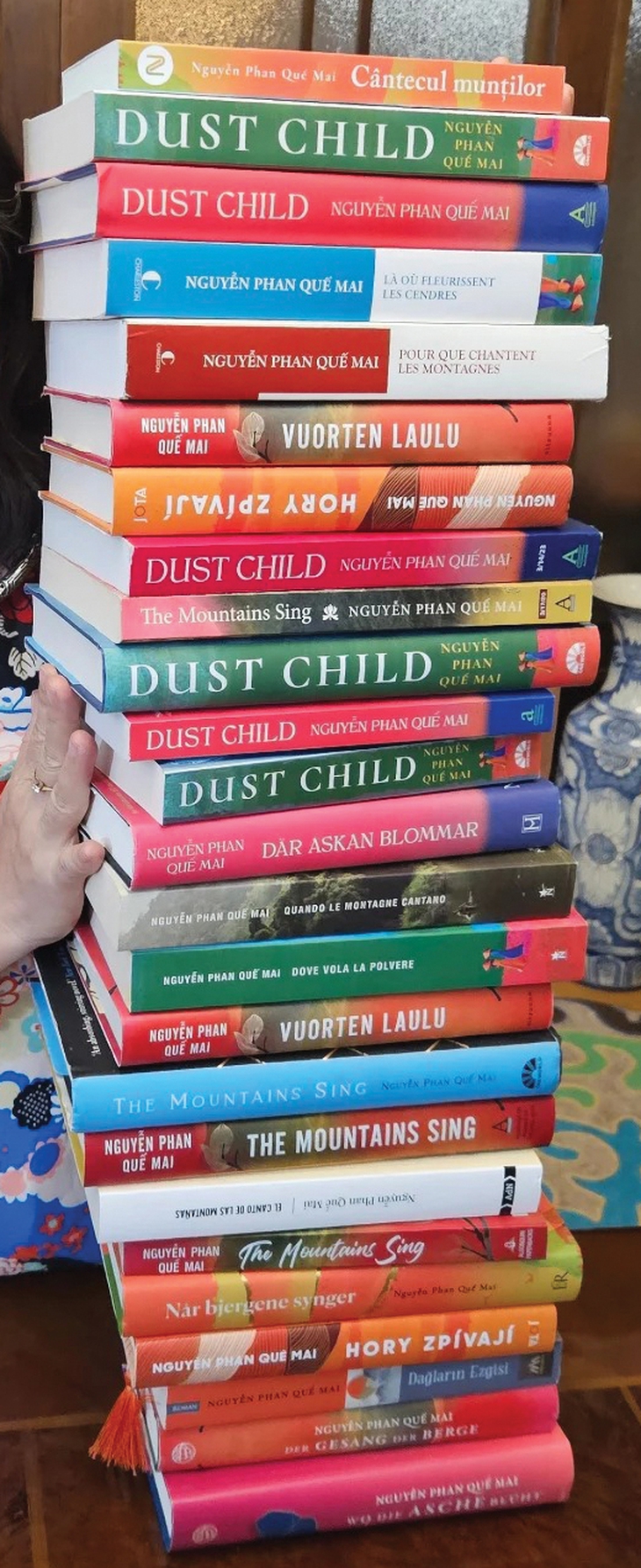

Nguyen Phan Que Mai's books have been translated into many languages.

The Mountains Sing and Dust Child were the beginning of my journey to write stories about peace. In The Mountains Sing, Huong, a 12-year-old girl, had to survive the American bombing of Hanoi in 1972. She longed to see peace because both her parents had to leave their family to join the war.

She said to herself: "Peace is the two sacred words on the wings of doves painted on the wall of my classroom. Peace is the green color in my dream - the green color of reunion when my parents return home. Peace is something simple, invisible, but most valuable to us".

I chose a 12-year-old girl as the narrator of the story about peace because when people are young, they have an open mind. Huong used to hate the Americans because they had dropped bombs on Kham Thien where her family lived.

But then when reading American books, she realized that Americans and Vietnamese people both love their families and cherish peaceful moments.

And she said to herself: "I wish that everyone on this earth listened to each other's stories, read each other's books, and saw the light of other cultures. If everyone did that, there would be no war on this earth."

In the book Dust Child, I have characters who have to go through the brutality of war to realize the value of peace.

In it, the character Dan Ashland is a former helicopter pilot who participated in the massacre of innocent children during the war in Vietnam. When he returned to Vietnam 47 years later, in 2016, he was extremely sad and found the light of forgiveness among the peace-loving and forgiving Vietnamese people.

During the journey to launch the two books, I received hundreds of letters from readers - veterans and victims of war. They shared with me images and stories of their experiences and their families. They showed me that I am not alone in my journey to tell stories of peace.

In the process of telling those stories of peace, I cannot help but mention mothers, sisters, and grandmothers. Perhaps women are the ones who suffer the most from war.

I touched that pain in the scream of a woman the first time I visited Quang Tri. That day, I was resting at a roadside tea shop with my Australian friends - white, blond people - when the scream startled us all.

Looking up, I saw a naked woman running towards us, screaming to my foreign friends that they must return her family. The villagers then dragged her away, and the tea seller told us that the woman had lost both her husband and child in the American bombing of Quang Tri.

The shock was so great that she went crazy, spending all day looking for her husband and children. The woman's tears have soaked into my writings, and I wish I could turn back time, to do something to ease her pain.

This April, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the end of the war, the book of poems The Color of Peace, a collection of poems I wrote directly in English, was released in the US. The book includes the poem "Quang Tri" with verses like the cry of a woman still echoing from many years ago: "The mother ran towards us/ The names of her two children filled her eyes/ The mother screamed "Where are my children?"/ The mother ran towards us/ Her husband's name was deep in her chest/ The mother screamed "Give me back my husband!".

The poetry collection The Color of Peace also brings the story of my friend, Trung, to international readers. I once witnessed my friend quietly burning incense before his father's portrait. The portrait showed a very young man: Trung's father had sacrificed himself in the war without ever knowing his son's face. For decades, Trung had traveled everywhere to find his father's grave.

Many trips through the mountains and forests, many efforts were in vain. Trung's mother grew older and older, and her only wish before she passed away was to find her husband's remains. Trung's story inspired me to write the poem Two Paths of Heaven and Earth, which appeared in the collection Color of Peace:

HEAVEN AND EARTH

White sky of anonymous graves

White earth of children looking for father's grave

Rain poured down on them

Children who have never known their father

Fathers Who Can't Come Home

The call "child" is still buried deep in the chest

The call of "father" for more than 30 years of restlessness

Tonight I hear the footsteps of father and son from two ends of the sky and earth.

The footsteps are bustling

Finding each other

Bloody footsteps

Lost each other through a million miles

Lost through thousands of centuries

Each foot I set on the land is placing on how many cold bodies in the ground?

Stepping on how many seas of tears of children who have not found their father's grave?

The white color of Truong Son cemetery always haunts me. I wish I could stay there longer, to burn incense at each grave. There are countless white graves, some of which are nameless. I sat next to a grave with two headstones: two families claimed this martyr as their son.

In the poetry collection The Color of Peace, I write about the anonymous graves and the pain that remains, lingering for many generations. I want to talk about the horrors of war, to call on everyone to do more to join hands in building peace.

The Color of Laughter

Writing about the pain of war, my poetry collection The Color of Peace tells a story about Vietnam, a country with 4,000 years of civilization. Therefore, I began the book with an article about Vietnam's poetic tradition, about Vietnam Poetry Day, and about the contribution of poetry in preserving peace for the Vietnamese people.

The book of poems ends with the story of my father, a man who went through war, suffered much pain and loss, and then became a literature teacher, passing on his love of peace and poetic inspiration to me.

With the help of peace-loving friends, I had the honor of participating in a "Color of Peace" journey through 22 cities in the US. I gave presentations at Columbia University (New York), Stanford University (San Francisco), UCLA (Los Angeles), Portland State University (Portland), UMASS Amherst (Amherst)...

At these events and at other events in libraries, bookstores, or cultural centers, I tell stories about a peace-loving Vietnam, stories about the lingering wounds on the body of Mother Vietnam (unexploded bombs, Agent Orange, etc.).

It was an honor to have great friends of Vietnam with me at these events. They were peace activist Ron Caver - who compiled and published the book Fight for Peace in Vietnam.

I had conversations with photographer Peter Steinhauer, who lives in Washington DC but has traveled to Vietnam many times to take pictures of the country and its people. I was deeply moved when talking to Craig McNamara, son of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara - who is considered the "chief architect" of the US involvement in the Vietnam War.

In his autobiography Because Our Fathers Lied, Craig McNamara frankly called his father a war criminal. I also had a conversation with Professor Wayne Karlin, who served as a helicopter gunner in Vietnam during the war, and then returned to Vietnam, actively participated in the anti-war movement, and spent the rest of his life translating, publishing and promoting Vietnamese literature...

At some events, I invited the American veteran poet Doug Rawlings to read his English poem, The Girl in Picture, which he wrote for Phan Thi Kim Phuc, who appeared in Nick Ut's photo "Napalm Girl."

And I read the Vietnamese translation of the poem, with its haunting lines: "If you're a Vietnam veteran, a wizened survivor/ she'll come to you across the decades/ casting a shadow across the dying light of your dreams/ she's still naked and nine, horror etched into her eyes/ Of course you'll have to ignore her/ if you want to survive the years/ but then your daughter turns nine/ and then your granddaughter turns nine."

I also read poems that I wrote about Agent Orange, about unexploded bombs, to call on Americans to join hands with projects of organizations to clear bombs and help victims of Agent Orange.

In addition to talking about the lingering effects of war and what people can do to help ease the pain, I want to talk about the value of peace, about the Vietnamese people's love for peace, and about what we can do to build lasting peace on this earth: that is, reading each other more, understanding each other more, respecting each other more, and listening to each other's stories.

The book of poems The Color of Peace carries my wish for lasting peace on earth, and so one of the main poems of this book, The Color of Peace, is dedicated to the people of Colombia, where armed violence is still rampant.

During the Medellin Poetry Festival many years ago, I set foot on a mountainside where hundreds of people had set up tents to escape the violence in their villages. I was moved to tears as they cooked traditional food for us, the international poets, and read poetry with us.

Then I wrote these verses: "And suddenly I felt like I belonged here/ to this land/ a land torn apart by civil war/ a land filled with the ghost of opium/ When the children and I together/ jumped rope, our steps light with hope/ I knew the dead were watching, protecting us/ And I saw the color of peace/ transforming into the color of laughter/ ringing on the lips/ of the children of Colombia".

The war has been over for fifty years. Someone said, let's stop talking about the war, the country has been at peace for a long time. But why does the war still roar in me when I see a family of Vietnamese martyrs spreading out a tarp, offering offerings and incense at the Plain of Jars, Xieng Khouang, in Laos?

Incense sticks were lit, along with tears and sobs. Prayers to heaven and earth and the souls of the martyrs to help them find their father's grave.

The farmers I met that day had been tightening their belts for more than 30 years to have enough money to hire a car and a guide to go to Laos to find the grave of their father - a Vietnamese soldier who died in the Plain of Jars. There are countless Vietnamese families who are traveling to Laos to find the graves of their loved ones. With very little information, they still search with a strong and burning hope.

Nguyen Phan Que Mai writes in Vietnamese and English and is the author of 13 books. Many of her poems have been set to music, including "The Fatherland Calls My Name" (music by Dinh Trung Can).

Her two English novels, The Mountains Sing and Dust Child, which explore war and call for peace, have been translated into 25 languages. She donated 100% of the royalties from her English poetry collection The Color of Peace to three organizations that clear unexploded bombs and assist victims of Agent Orange in Vietnam.

Nguyen Phan Que Mai has received many domestic and international literary awards, including second prize in the Dayton Peace Prize (the first and only American Literary Award recognizing the power of literature in promoting peace).

Source: https://tuoitre.vn/mau-hoa-binh-2025042716182254.htm

![[Photo] General Secretary To Lam attends the 80th Anniversary of the Cultural Sector's Traditional Day](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/8/23/7a88e6b58502490aa153adf8f0eec2b2)

Comment (0)